Joseph Corry - Observations Upon the Windward Coast of Africa (1807)

...

CHAPTER III.

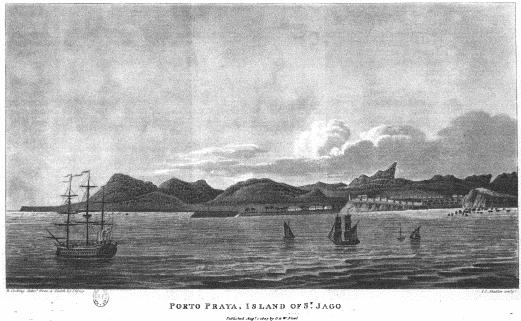

An Excursion to the Main Land.—Visit to King Marraboo.—Anecdotes of this Chief.—Another Excursion, accompanied by Mr. Hamilton.—A shooting Party, accompanied by Marraboo's Son, Alexander, and other Chiefs.—Reflections upon Information obtained from them, relative to this Part of the Coast, and at Goree.—Embark in his Majesty's Sloop of War, the Eugenie, which convoyed Mr. Mungo Park in the Brig Crescent, to the River Gambia, on his late Mission to the Interior of Africa.—Observations on that Subject.—Arrive in Porto Praya Bay, in the Island of St. Jago.—Some Remarks upon that Island.—Departure from thence to England, and safe arrival at Portsmouth.

A few days after the arrival of the Lark at the island of Goree, accompanied by a party of the officers of that ship, I made an excursion upon the main land: we set out from the ship early in the morning, for Decar, the capital of a chief or king, named Marraboo: we arrived before he had moved abroad, and, after going through winding narrow paths or streets, we were conducted by one of his people to his palace, a wretched hovel, built with mud, and thatched with bamboo. In our way to this miserable habitation of royalty, a confused sound of voices issued forth from almost every hut we passed, which originated from their inhabitants vociferating their morning orisons to Allah and Mahomet; their religion being an heterogeneous system of Mahomedanism, associated with superstitious idolatry, incantations, and charms.

We found Marraboo's head men and priests assembled before his majesty's dwelling to give him service, and to offer him their morning's salutation. At length he made his appearance, followed by several of the officers of the palace, carrying skins of wild beasts, and mats, which upon enquiry, I found to have composed the royal bed, spread out upon a little hurdle, erected about a foot and a half high, interwoven with bamboo canes: my attention was much engaged with this novel sight; and I could not contemplate the venerable old man, surrounded by his chiefs, without conceiving I beheld one of the patriarchs of old, in their primaeval state. After his chiefs had paid their obeisance, I presumed, accompanied by my friends, to approach the royal presence; when he discovered us among the group, his countenance underwent an entire change, expressive of reserve and surprise, exclaiming, "What did I want with Marraboo?" With great humility I replied, "I be Englishman, come from King George's country, his brother, to give him service." He replied with quickness, "I be very glad to see you, what service have you brought?" I was aware of this tax upon my civility, and replied, that "I make him good service;" which in plain English was, that I shall make you a good present. He then conversed with more freedom relative to his country, government, localities, and religion; I suggested to him that "I understood he was a powerful king, and a great warrior, had many wives and children, that he ruled over much people, and a fine country, that I hear he get much head, that he far pass any of his enemies, and that I be very happy to look so great a king:" or, in other words, that I understood he was a great general, was very rich, was more wise than all his contemporary chiefs, and that it gave me much pleasure to pay my respects to so great a prince: but the former idiom of language is best adapted to convey meaning to the interpreters of the chiefs of Africa, in whatever tongue it may be spoken; being that which they use in translation; and when they are addressed in this phraseology, they convey their ideas with more perspicuity and literal interpretation. But to return to the dialogue.

Marraboo.—"I be very glad to look you for that, I have much trouble all my life—great deal of war—my son some time since killed in battle." This was accompanied by such a melancholy expression of countenance, that could not fail to excite my compassion, I therefore avoided touching more on the subject of his wars; only observing, "that I hear he be too much for all his enemies, and that he build great wall that keep his town and people safe."

Marraboo.—"The king of Darnel's people cannot pass that—they all be killed—they come there sometimes, but always go back again." My curiosity was excited to obtain the history of this enchanted wall, which on my approach to the town, I had discovered to be apparently little more than three or four feet high, and situated within the verge of their wells of fresh water, open at several places, and without any defence.

Upon enquiry, I found that Marraboo had been early in life fetish man, or high priest, to Damel, king of Cayor, a very powerful chief bordering upon the Senegal, and that he had artfully contrived to gain over to his interest a number of adherents, who, in process of time, became formidable, rebelled against their lawful sovereign, and took possession of that part of the country towards Cape Verd: to strengthen their position, Marraboo caused a wall to be erected, commencing from the sea shore, and extending towards the Cape; which, in the estimation of the natives, and in consequence of his sacerdotal office, incantations, and charms, was rendered invulnerable: the hypocritical priest well knew the natural disposition of his countrymen, and the effect his exorcisms would produce upon their minds; which operated so effectually, that when his army was beaten by the powerful Damel, they uniformly retired behind their exorcised heap of stones, which in a moment stopt their enemy's career, and struck them with such dread, that they immediately retired to their country, leaving their impotent enemy in quiet possession of his usurped territory; whom otherwise they might have annihilated with the greatest facility. Superstition is a delusion very prevalent in Africa; and its powerful influence upon the human mind is forcibly illustrated by the foregoing instance.

When I enquired of Marraboo the nature of his belief in a supreme being, his observations were confused and perplexed, having no perspicuous conception of his attributes or perfections, but an indistinct combination of incomprehensibility; and to sum up the whole, he remarked, "that he pass all men, and was not born of woman."

A few days after the abovementioned visit, I made another excursion to the main land, accompanied by Mr. Hamilton, and one of the principal inhabitants of Goree, named Martin. We landed at a small native town, called after the island, Goree Town. When we came on shore, we were immediately surrounded by natives, who surveyed us with great curiosity and attention. We had prepared ourselves with fowling-pieces and shooting equipage, with the view of penetrating into the interior country: in pursuance of our design, we dispatched a messenger to Decar, with a request that we might be supplied with attendants and horses: our solicitation was promptly complied with; and Alexander, Marraboo's son, speedily made his appearance with two horses, attended by several chiefs and head men. Our cavalcade made a most grotesque exhibition; Mr. Hamilton and myself being on horseback, followed by Alexander and his attendants on foot, in their native accoutrements and shooting apparatus. My seat was not the most easy, neither was my horse very correct in his paces; the saddle being scarcely long enough to admit me, with a projection behind, intended as a security from falling backwards: the stirrups were formed of a thin plate of iron, about three or four inches broad, and so small, that I could scarcely squeeze my feet into them. In our progress we killed several birds, of a species unknown in Europe, and of a most beautiful plumage; one of which, a little larger than the partridge in England, was armed with a sharp dart or weapon projecting from the pinion, as if designed by nature to operate as a guard against its enemies. Our associates rendered us every friendly attention, and evinced great anxiety to contribute to our sport; and proved themselves skilful and expert marksmen. The country abounded with a multiplicity of trees and plants, which would no doubt have amply rewarded the researches of the botanist, and scientific investigator. The fatigue I had undergone, and the oppressive heat of the sun, so completely overpowered me, by the time of our return to Goree Town, that I felt myself attacked by a violent fever; in this situation I was attended with every tenderness and solicitude by the females; some bringing me a calabash of milk, others spreading me a mat to repose upon, and all uniting in kind offices: it is from them alone that man derives his highest happiness in this life; and in all situations to which he is exposed, they are the assuasive agents by whom his sorrows are soothed, his sufferings alleviated, and his griefs subdued; while compassion is their prominent characteristic, and sympathy a leading principle of their minds.

The attention of these kind beings, and the affectionate offices of my friend, operating upon a naturally good constitution, soon enabled me to overcome the disease, and to return again to Goree. During the remaining part of my stay there, I was vigilantly employed in procuring every information relative to this part of the coast, and through the intelligence of several of the native inhabitants and traders, I am enabled to submit the following remarks.

To elucidate, with perspicuity, the deep impression I feel of the importance of this district of the Windward Coast, in obtaining a facility of intercourse with the interior, combining such a variety of local advantage, by which our ascendency may be preserved, and our commercial relations improved, is an undertaking, the difficulties of which I duly appreciate; and I am aware that I have to combat many prejudices and grounds of opposition to the system I conceive to be practicable, to develope the various stores of wealth with which Africa abounds, and to improve the intellectual faculties of its native inhabitants.

That a situation so highly valuable as the Senegal, and its contiguous auxiliary, the island of Goree, has been so overlooked, is certainly a subject of great surprise, and deep regret. While visionary and impracticable efforts have been resorted to penetrate into the interior of Africa, we have strangely neglected the maritime situations, which abound with multifarious objects of commerce, and valuable productions, inviting our interference to extricate them from their dormant state; and the consideration apparently has been overlooked, that the barbarism of the natives on the frontiers must first be subdued by enlightened example, before the path of research can be opened to the interior.

We have several recent occurrences to lament, where the most enterprising efforts have failed, through the inherent jealousies of the natives, and their ferocious character; and, therefore, it is expedient to commence experiments in the maritime countries, as the most eligible points from whence operative influence is to make its progress, civilization display itself among the inhabitants, and a facility of intercourse be attained with the interior. So long as this powerful barrier remains in its present condition, it will continue unexplored; and our intercourse with its more improved tribes must remain obscured, by the forcible opposition of the frontier; and these immense regions, with their abundant natural resources, continue unknown to the civilized world. The inhabitants of the sea coast are always more fierce and savage than those more remote and insular: all travellers and voyagers, who have visited mankind in their barbarous state, must substantiate this fact: and the history of nations and states clearly demonstrates, that the never-failing influence of commerce and agriculture united, has emanated from the frontiers, and progressively spread their blessings into the interior countries. View our own now envied greatness, and the condition in which our forefathers lived, absorbed in idolatry and ignorance, and it will unquestionably appear, that our exalted state of being has arisen from the introduction of the civilized arts of life, the commerce which our local situation has invited to our shores, and our agricultural industry.

Within the district now in contemplation, flows the river of Senegal, with its valuable gum trade; the Gambia, abounding with innumerable objects of commerce, such as indigo, and a great variety of plants for staining, of peculiar properties, timber, wax, ivory, &c.; the Rio Grande, Rio Noonez, Rio Pongo, &c. all greatly productive, and their borders inhabited by the Jolliffs, the Foollahs, the Susees, the Mandingos, and other inferior nations, and communicating, as is now generally believed, with the river Niger, which introduces us to the interior of this great continent; the whole presenting an animating prospect to the distinguished enterprise of our country.

That these advantages should be neglected, is, as I have before said, subject of deep regret, and are the objects which I would entreat my countrymen to contemplate, as the most eligible to attain a knowledge of this important quarter of the globe, and to introduce civilization among its numerous inhabitants; by which means, our enemies will be excluded from that emolument and acquirement, which we supinely overlook and abandon to contingencies.

The island of Goree lies between the French settlement of the Senegal and the river Gambia, and therefore is a very appropriate local station to aid in forming a general system of operation from Cape Verd to Cape Palmas, subject to one administration and control. The administrative authority, I would recommend to be established in the river of Sierra Leone, as a central situation, from whence evolution is to proceed with requisite facility, and a ready intercourse be maintained throughout the whole of the Windward Coast; and as intermediate situations, I would propose the rivers Gambia, Rio Noonez, Rio Pongo, and Isles de Loss, to the northward; and to the southward, the Bannana Islands, the Galinhas, Bassau, John's River, &c. to Cape Palmas; or such of them as would be found, upon investigation, best calculated to promote the resources of this extensive coast.

The supreme jurisdiction in the river Sierra Leone, with auxiliaries established to influence the trade of the foregoing rivers, form the outlines of my plan, to be supported by an adequate military force, and organized upon principles which I have hereafter to explain in the course of my narrative.

Having an opportunity to sail for England, in his Majesty's sloop of war the Eugenie, commanded by Charles Webb, Esq. as it was uncertain at what time the Lark was to proceed, I availed myself of that officer's kind permission to embark, accompanied by surgeon Thomas Burrowes and his lady.

The Eugenie had been dispatched for England to convoy the Crescent transport brig, with Mr. Mungo Park on board, to the river Gambia, upon his late mission to the interior of Africa. Captain Webb did not conceive it prudent, nor indeed was it expedient, to proceed higher up the river than Jillifree, and dispatched the Crescent as far as Kaya, about 150 miles from the capes of the river, where Mr. Park landed with his associates, viz. his surgeon, botanist, draftsman, and about 40 soldiers, commanded by an officer obtained from the royal African corps at Goree, by the order of Government.

Nothing could have been more injudicious than attempting this ardoous undertaking, with any force assuming a military appearance. The natives of Africa are extremely jealous of white men, savage and ferocious in their manners, and in the utmost degree tenacious of any encroachment upon their country. This unhappy mistake may deprive the world of the researches of this intelligent and persevering traveller, who certainly merits the esteem of his country, and who, it is to be feared, may fall a victim to a misconceived plan, and mistaken procedure.

Although anxious to embark, yet I could not take my departure without sensibly feeling and expressing my sense of obligation for the many attentions I had to acknowledge from the officers of the garrison, and also to several of the native inhabitants, among whom were Peppin, Martin, St. John, and others; the latter, I am sorry to say, was in a bad state of health; I am much indebted to him for his judicious remarks, and very intelligent observations. This native received his education in France, and has acquired a very superior intelligence relative to the present condition of his country.

Accompanied by Mr. Hamilton, my hospitable and friendly host, and several of the officers of the Lark, I embarked on board the Eugenie, on the 31st of May, and arrived in Porto Praya Bay on the 3d of June.

The town of Porto Praya is situated upon a plain, forming a height from the sea, level with the fort, and is a most wretched place, with a very weak and vulnerable fortification. In the roads there is good anchorage for shipping, opposite to Quail island, and for smaller vessels nearer the shore. It has a governmenthouse, a catholic chapel, a market place, and jail, built with stone; and is now the residence of the government of the island of St. Jago, subject to the crown of Portugul. Formerly the governor's place of abode was at the town of St. Jago, upon the opposite side of the island: his title is that of governor-general of the islands, comprehending Mayo, Fogo, &c.

Mayo is remarkable for its salt, which is cast on shore by the rollers or heavy seas, which at certain periods prevail, and run uncommonly high. The heat of the sun operating upon the saline particles, produces the salt, which the inhabitants collect in heaps for sale. We anchored at Mayo for some hours, and a number of vessels were lying in the roads, chiefly Americans, taking in this article; it is a very rocky and dangerous anchorage; we, however, found the traders were willing to undergo the risque, from the cheapness of the commodity they were in quest of.

It is a most sorry place, with scarce a vestige of vegetation upon its surface, and its inhabitants apparently live in the greatest misery. They are governed by a black man, subject to the administration of St. Jago.

The military force of St. Jago is by no means either formidable in numbers or discipline, and exhibits a most complete picture of despicable wretchedness.

A black officer, of the name of Vincent, conducted as to the governor, who received us with politeness, and gave us an invitation to dinner. The town and garrison were quite in a state of activity and bustle; an officer of high rank and long residence among them had just paid the debt of nature, and his body was laid in state in the chapel, in all his paraphernalia. The greater part of the monks from the monastery of St. Jago were assembled upon the occasion, to sing requiems for his soul; and the scene was truly solemn and impressive. We met these ministers of religion at dinner, but how changed from that gravity of demeanor which distinguished them in their acts of external worship. The governor's excellent Madeira was taken in the most genuine spirit of devotion, accompanied by fervent exclamations upon its excellent qualities. Upon perceiving this holy fervency in the pious fraternity, we plied them closely, and frequently joined them in flowing bumpers, until their ardour began to sink into brutal stupidity, and the morning's hymns were changed into revelry and bacchanalian roar.

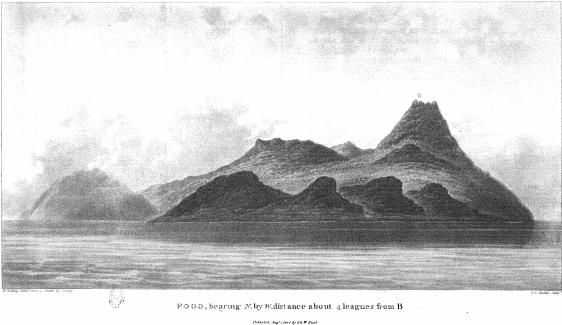

[Illustration: FOGO, bearing N. by W. distance about 4 leagues from B Published Aug 1 1807 by G & W Nicol]

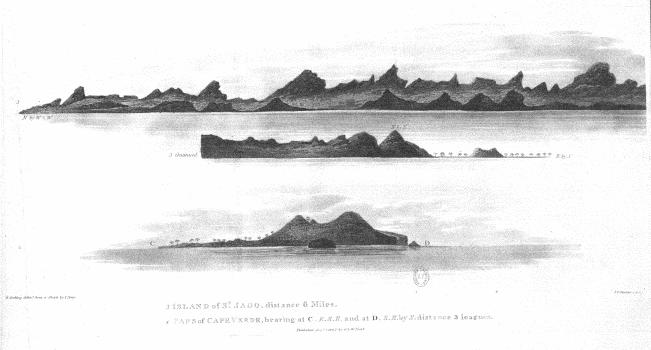

[Illustration: 3 ISLAND of ST. IAGO, distance 6 Miles. 4. PAPS of CAPE VERDE, bearing at C, N.N.E. and at D, S.E. by S. distance 3 leagues. Published Aug 1 1807 by G & W Nicol]

This, however, was rather a tax upon the governor's hospitality, as it deprived him of his Ciesta, a common practice with him, almost immediately after the cloth is withdrawn. When we came ashore the next morning, we were highly entertained with the anecdotes related to us of the pranks performed during the night by the convivial priests, many of whom were unable to fulfil the duties of the altar at the usual hour of prayer.

The natives of St. Jago, with those of the neighbouring islands, are mostly black, or of a mixed colour, very encroaching in their manners, and much addicted to knavery. The island is extremely rocky and uneven, but the vallies are fertile. The inhabitants raise cotton, and they have several sugar works; the quantity they raise of both, does not, however, much exceed their own consumption, but there is no doubt that it might be considerably augmented by industry, even for exportation; but the natives are indolent, and extremely listless in their habits. The only inducement in touching at this island is, to procure water and provisions: the former is good, and the latter consists in hogs, turkeys, ducks, poultry, &c. but frequently, after they have been visited by a fleet, a great scarcity prevails.

The commodities the natives require as payment may be purchased at Rag Fair, being extremely partial to cast off wearing apparel of every description.

The men are extremely slovenly in their dress; but the women are rather more correct and uniform, those of the better condition being habited in muslin, and their hair ornamented, and neatly plaited.

They manufacture a narrow cloth of silk and cotton, which is in high estimation among them, and its exportation is prohibited, except to Portugal. Considerable ingenuity is displayed in this manufacture, which is performed in a loom, differing very little from that used by the ruder inhabitants of the coast of Africa, and similar to the garter loom in England. They have horses and mules well adapted to their roads and rugged paths, which they ride most furiously, particularly the military, who advance at full speed to a stone wall, or the side of a house, merely to shew their dexterity in halting.

After being detained here for several days in taking in stock and provisions, we again weighed with the Crescent brig, and a sloop from Gambia, bound to London, under our convoy, and after a tedious and very anxious passage, arrived at Portsmouth on the 4th of August. We were detained under quarantine until the return of post from London, and proceeded on shore the following day. There is something in natale solum which charms the soul after a period of absence, and operates so powerfully, as to fill it with indescribable sensations and delight. Every object and scene appeals so forcibly to the senses, enraptures the eye, and so sweetly attunes the mind, as to place this feeling among even the extacies of our nature, and; the most refined we are capable of enjoying.

It is this love of his country which stimulates man to the noblest deeds; and, leaving all other considerations, only obedient to its call, separates him from his most tender connections, and makes him risque his life in its defence.

"Where'er we roam, whatever realms to see,

Our hearts untravell'd fondly turn to thee;

Still to our country turn, with ceaseless pain,

And drag, at each remove, a lengthening chain."

GOLDSMITH.

...

CHAPTER VIII.

What the Author conceives should be the System of Establishment to make effectual the Operations from Cape Verde to Cape Palmas.—Reasons for subjecting the Whole to one Superior and controlling Administration.—The Situations, in his Estimation, where principal Depots may be established, and auxiliary Factories placed, &c. &c.

What I have already said respecting the coast from Cape Verde to Cape Palmas, may be sufficient to convey a tolerably just and general idea of the religion, customs, and character of the inhabitants, the commercial resources with which it abounds, and the system to be pursued to unite commerce with the claims of humanity in one harmonious compact.

I am persuaded there is no situation on the Windward Coast of Africa more calculated, or more advantageously situated, than the river of Sierra Leone to influence and command an enlarged portion of the continent of Africa.

This part of Africa, as ascertained by Mr. Park, communicates, by its rivers to the Niger, and introduces us to the interior of this great continent; and, from other sources of information, Foolahs, Mandingos, &c. I am enabled to confirm the statement given in one of the reports of the Sierra Leone Company, that from Teembo, about 270 miles interior to the entrance of the Rio Noonez, and the capital of the Foolah king, a path of communication exists through the kingdoms of Bellia, Bourea, Munda, Segoo (where there are too strong grounds to believe that the enterprising spirit of Mr. Park ceased its researches in this world), Soofundoo to Genah, and from thence to Tombuctoo, described as extremely rich and populous. The distance from Teembo to Tombuctoo the natives estimate at about four moons' journey, which at 20 miles per day, calculating 30 days to each moon, is equal to 2,400 miles. This distance in a country like Africa, obscured by every impediment which forests, desarts, and intense climate can oppose to the traveller, is immense; and when it is considered that in addition to these, he has to contend with the barbarism of the inhabitants, it is a subject for serious deliberation, before the investigation of its natural history and commercial resources is undertaken. But it also displays an animating field of enterprise to obtain a free intercourse with this unbounded space, and if, at a future day, we should traverse it with freedom and safety, the whole of Africa might thereby be enlightened, and its mysteries developed to the civilized world.

I have therefore conceived the expediency of submitting all the enterprises and operations of the United Kingdom to the influence of a supreme direction and government in the river of Sierra Leone. No doubt many contradictory opinions may prevail upon this subject, and upon the outline I have previously submitted on the most eligible plan of introducing civilization into Africa; but the detail of all my motives and reasons would occupy too large a space; I shall therefore proceed to instance some local circumstances and political reasons why I make the proposition.

From what I have said respecting the path which Smart, of the Rochell branch of the river Sierra Leone, has now under his authority, and can open and shut at pleasure, communicating with the extensive country of the Foolahs, whose king (as the Sierra Leone agents are well aware of, but who was strangely and unaccountably neglected by them) is well disposed to aid, by prudent application, all advances towards the civilization of his country, it is evident that an immense commerce, extending northward to Cape Verde, and southward to Cape Palmas, on the coasts, and from the interior countries, might be maintained.

By light vessels and schooners, drawing from 6 to 8 feet water, a continued activity might be kept up in the maritime situations and rivers, and a correspondence by land might be conducted by post natives, who travel from 20 to 30 miles per day, to all parts of the interior countries.

From the Island of Goree a correspondence with the river Gambia, and a watchful vigilance over the settlement of the French in the Senegal would be maintained both by land and sea, which, with a well chosen position, central from Cape Sierra Leone, to Cape Palmas, would combine a regular system of operation, concentrating in the river Sierra Leone. In addition to these three principal depots, it would be requisite to establish factories, and places of defence to the northward, on the rivers Scarcies and Kissey, at the Isles de Loss, the rivers Dembia, Rio Pongo, Rio Grande, Rio Noonez, and Gambia; and to leeward, on the rivers Sherbro, Galhinas, Cape Mount, Junk river, John's river, Bassau, &c. or in other commanding positions towards Cape Palmas. The expense of these auxiliary establishments and forts would be inconsiderable, compared with the objects they would attain, the chief requisite being regular and well supplied assortments of goods, and a wise system of organization adapted to circumstances.

The navigation of these rivers, and habits of conciliation and friendship with the chiefs resident upon them, and towards the interior, it may here be perceived, are the only practicable measures, under the auspicious control of Government, to retain our commerce with Africa, to civilize its inhabitants, and explore its hidden wealth; and are the most favourable, also, towards our operations in the countries on this continent; while the various natives attached to this pursuit, would aid, by wise management, in influencing the inhabitants, where our researches and pursuits might carry us, and eventually conduct us to the centre of Africa, from thence to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, and the banks of the Nile. I trust it will here also appear that the means of acting, and the important advantages to be derived therefrom, are neither illusive nor impracticable.

It is to be lamented, that, in undertakings of this kind, men of limited genius, of no experience in business, and incapable of acting with unanimity, have been too frequently employed; who are governed more by caprice than principle, and are consequently seldom able to reduce their ideas into practice, and allow their passions to predominate over the maxims of duty. Delicacy in managing the humours and interests of men is the art requisite to successful operation.

May it be remembered, that if civilization and our ascendency prevail in Africa, and if the first essays we make to extend our relations with that country are successful, we attach to the civilized world one-fourth of the habitable globe, and its infinite resources. It therefore becomes a subject of great magnitude, to commence and form a system of operation, to collect the means of this immense extent, and the propriety of subjecting the whole to a similarity of views, and co-operation under one controlling administration.

The precipitate abolition of the slave trade will reduce our affairs in Africa, to a contracted and unproductive compass, in its present condition; therefore if we attach any consequence to this quarter of the globe, it will be expedient to endeavour to discover new scources [**Note: sources] of commercial wealth and industry.

Coffee, cotton, the sugar cane, cacao, indigo, rice, tobacco, aromatic plants and trees, &c. first offer themselves to, our attention in wild exuberance. And these, in my humble opinion, are the only rational means to bring Africa into a state of civilization, and to abolish slavery.

I recommend one administration under the patronage of Government, in the Sierra Leone river, to guard against a want of unity in the number of petty establishments that may otherwise exist on the coast, which from jealousies and interests varying in different directions, produce operations of a contradictory nature, and the first necessary step, is to be well acquainted with the character and dispositions, of the natives, and the localities of the maritime situations; for without combined enterprises, I venture to predict we are now excluded from the commerce of Africa.

I trust that my system will be examined in all its points, with dispassionate impartiality before it is rejected; and if others more competent to the task, devise more eligible means to promote the views of humanity and commerce, I shall feel happy to have agitated the subject, and rejoice at every means, to rescue so important a matter to the interests of mankind.

The commandant of Goree, I would propose as second in command, with delegated powers to control all the operations in the countries bordering on the Senegal, and the river Gambia; and an annual inspection directed by him, throughout this district. The intermediate countries from the Rio Noonez to Cape Mount would come immediately under the examination of the central and administrative government of Sierra Leone, and the third division under the authority of another command at a position chosen between Cape Mount, and Cape Palmas.

The military protection of the establishments, as I have here recommended, would neither require great exertions, or numbers. Goree certainly claims peculiar attention. Its fortifications should be repaired, and the guns rendered more complete, and tanks for water should be in a perfect state to guard against the want of this necessary article from the main land, which, as before noticed, is liable to be cut off at any period by the enemy. The convenience, airy and healthy construction of the barracks and hospitals, claim the most minute attention and care. Under skilful superintendance in these important departments, the health of the troops might be preserved, and objects of defence realized with a very inconsiderable military establishment. But as government must be well informed by its officers, both military and naval in these points, it would be indecorous in me to enlarge on the subject. Lieut. Colonel Lloyd, from his long residence, and intimacy with a great portion of the Windward Coast, possesses ample information. And the naval officers, who from time to time have visited it, have, no doubt, furnished every document necessary to complete an effective naval protection. A regular system of defence, adapted to the jurisdiction of the Sierra Leone, and delegated establishment between Cape Mount and Cape Palmas, are also obviously requisite. The establishments that would be eligible for the purposes of defence, are confined to the three foregoing principal positions, and they have little to perform that is either difficult or embarrassing. It may not, however, be considered as going beyond the bounds of propriety to hint, that a great portion of the soldiers charged with defence, should be able engineers and gunners, and a few cavalry might be occasionally found useful. To complete the entire plan, and exclude our enemies from every point, from Cape Blanco to Cape Palmas, the possession of the French establishment at the Isle of Louis in the Senegal, is an abject of serious contemplation, and no doubt might be attained with great facility by even a small force. The unhealthy consequences to a military force attached to this place might be greatly removed by superior convenience in the hospitals, barracks, and other departments of residence; and in a commercial point of view, its advantages are too well ascertained for me to obtrude any observations.

The bricks necessary for building may be procured in the country, lime from oyster shells, &c. wood and other materials at a very inconsiderable expense; and as the usual mode of payment, is in bars of goods, instead of money, the nominal amount would thereby be greatly lessened.

...